Why the Younger Generation Struggles with Math – A Look at Changing Education and Work Ethic

Since actively participating in programmer recruitment, I have noticed a particular trend—every year, newcomers (entry-level and junior) seem less prepared after university. One thing I have already written about is that they simply have not dedicated enough hours to learning and self-improvement, and they arrive with the mindset that university alone is enough.

On the other hand, even with such an attitude, an averagely talented newcomer with logical thinking skills should still reach an appropriate level of knowledge, even without extra effort. Yet, we constantly see articles about how math exams are becoming a significant hurdle for high school graduates… So, where are the roots of this issue? I believe I have an answer.

Spring and summer are approaching, which means we will once again hear stories of high school graduates shedding tears and struggling, about how difficult it was to pass the twelfth-grade math exam—or that it was simply an impossible mission because “we have never seen such tasks before,” “the problems were like Olympiad-level,” and “everything is unfair.”

“My career is over!” students will say once again.

I have been thinking about this issue, and while writing my story on LinkedIn about my journey from programmer to CEO, specific thoughts persisted.

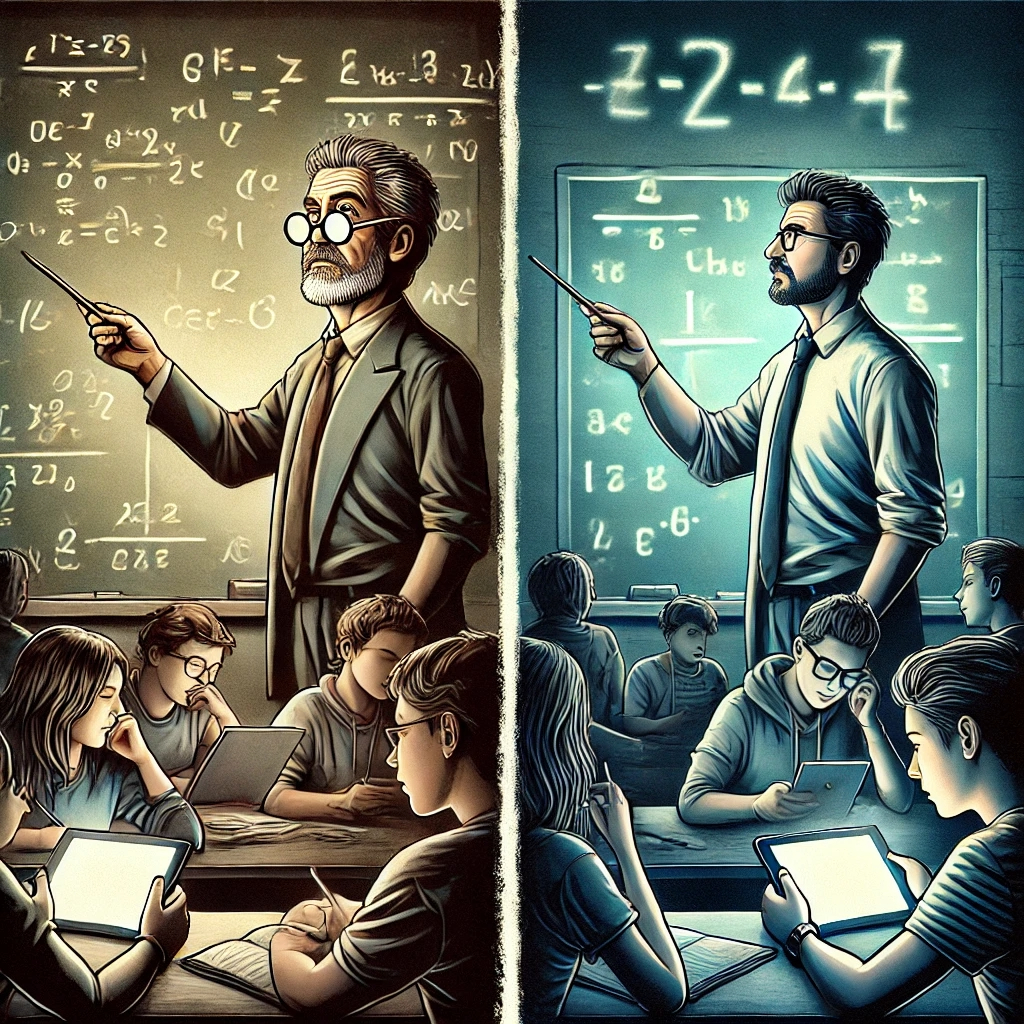

Do You Remember When Everyone Feared the Math Teacher?

Let’s be honest—there was silence when you walked into a math class. Unlike geography or history classes, math lessons had a different atmosphere. I dare to say that very few students threw paper airplanes or talked nonstop in math class. Math teachers were different. But how?

I must say, and I am incredibly grateful—perhaps to fate—that I had the opportunity to learn from, in my opinion, some of the best math teachers in Klaipėda: first at “Versmė” Primary School, later at “Ąžuolynas” Gymnasium, and finally at Kaunas University of Technology. If not for them, I probably wouldn’t have developed my algorithmic thinking, logical reasoning, and mathematical skills, because I never considered myself exceptionally talented—just an average student in this field. At least compared to some of my classmates.

These teachers managed to cultivate an undeniable authority in the classroom—a respectful fear that serious work was happening here, and there was no room for mischief. At the same time, these teachers and lecturers were true specialists in their fields.

I don’t know whether character is separate from skill, or if respect for competence played a role, but even those classmates who were completely uninterested in any other subjects—who would blow their noses until they bled in history class or even eat chalk—somehow managed to learn math from these teachers better than today’s average student at a prestigious gymnasium.

What’s the Secret?

The first answer that comes to mind is that such teachers simply no longer exist. There are no more highly skilled, talented, and competent math teachers. And there are no more strong university lecturers.

Each of my teachers, both in school and university, made sharp comments about the new generation of teachers—how these newcomers required guidance like schoolchildren themselves and struggled to solve more complex problems independently.

It’s a pity for students who were naturally talented in math but had to solve problems on the board for their teachers because the teachers themselves couldn’t. I have heard similar stories—not just one or two.

Even as a first-year university student, my peers often said, “I got into university because I used to solve problems for my math teacher on the board and explain the material to my classmates.”

A Clear Teaching System

Those old-school teachers seemed to have a well-established teaching system—refined over years of practice. You could feel it in the way tests and exams were structured: often, you would receive problems that were essentially the same as those you had practiced before, just slightly modified.

These tests didn’t just check rote memorization but accurate understanding. You could solve any similar math problem if you grasped the core principles. And they taught in a way that made sure you understood—not just memorized. After all, mathematics is not about blind repetition.

More Work, More Learning

Another thing I realized upon reflection is that, regardless of a teacher’s skill, knowledge, or ability to explain, they gave much homework. There was simply no other way—you had to practice solving problems.

For example, at Klaipėda’s “Ąžuolynas” Gymnasium, we had something called “credit tests”—we would receive about 50 problems to solve at home, and then once a month, we would have a test with the same issues.

If you were naturally talented (and some were), you could skip the practice, walk into the test, and solve the problems correctly. But those who lacked confidence would diligently work through them at home to ensure they knew the methods, tested their knowledge, and learned what they didn’t yet understand.

Ultimately, even students who struggled with math could get top scores—simply by putting in the work.

I don’t know whether today’s parents would accept such a system. Would they argue, “Why should my child do so much homework?” or “Why should they be forced to solve problems that are not directly assigned?”

A Cultural Shift

Finally, our society has distanced itself from this type of education.

At the beginning of this article, I mentioned our fear of our math teachers. At least, I certainly felt it. But it was a respectful fear—an understanding that this was a serious subject where discipline mattered.

Some reading this might be shaking their heads, saying, “That’s outdated thinking! Students shouldn’t fear their teachers!”

And yet, when those strict, authoritative math teachers disappeared, so did high math exam scores.

Our society has changed. We no longer want strict, demanding teachers who hold students accountable. We prefer everything to be soft, accommodating, and non-intimidating.

Today, if a university math professor asked the same question five times in a row until a student answered correctly, people would probably say it’s unacceptable. But this persistence builds an invaluable skill—the ability to communicate precisely in mathematics, business, leadership, and beyond.

When my physics teacher used to say, “I don’t care about excuses—gymnasium is for results, not just trying,” it was a life lesson. No matter where you go, you can’t just apologize for mistakes and expect everything to be okay.

From that teacher, I learned to view problems through the lenses of “given” and “to be solved,” and this structured way of thinking still helps me today in solving complex challenges.

Final Thought

So why are today’s young programmers weaker? Is it because true experts have retired?

Or is it because students today put in less effort and don’t understand that real success requires time and dedication?

Most importantly, has our society shifted to a mindset where anyone truly competent and unafraid to show it is seen as not fitting into today’s “soft values”?

Are we living in a self-deceptive, sugar-coated world while still complaining that things aren’t fair?

Do we resist hard work and feel frustrated when we don’t get the desired results?

Comments

[…] week ago, I wrote a post about why high school graduates struggle with mathematics exams. This time, I’d like to explore a different topic: why newcomers to the information […]

[…] couple of weeks ago, I wrote about why it’s becoming increasingly difficult for students to pass math exams. Last week, I continued my thoughts on the challenges faced by those trying to start a career in […]