How Does One Become a Toxic Leader?

In my previous post, I shared the idea that despite our modest earnings—split between not just one but two or even three people—we had everything an honest IT company needed: an office in the heart of Kaunas, snacks, enjoyable leisure activities, and the ambition to provide employees with experiences they had never tried before. And yet, the employees were unhappy. Why?

Or, to put it another way—my story of becoming a toxic leader.

LinkedIn is a bubble of good leadership and best practices. Everyone seems to know how to be the world’s most outstanding leader, empowering their team to achieve more significant results. That is until they must be that kind of leader within their team and do the work.

I have officially been a leader for ten years, but I only truly started learning how to be one in my company’s sixth or seventh year. So, what were those early years like?

The Context

The background to my journey can be found in my previous posts, where I’ve shared how, as a child from a simple family, reading about Bill Gates and others’ successes made me dream of becoming like them. My dream started with the American symbol of luxury and authority—the Cadillac Escalade. But dreams aside, unpaid work writing blogs, immersing myself in IT, and a series of accidental events taught me that success requires working hard, planning, and striving to turn dreams into reality.

Since I had nothing to lose, I was the only solution to my problem. Brian Tracy’s audiobooks, shifting my perspective from external validation to internal growth, and empowering myself with the realization that I can, were the turning points. And this mindset worked perfectly… until I had to start delegating tasks and working with others.

That meant I was responsible not just for myself but for the results of others as well.

The second part of my background is that I was fortunate to work with fantastic examples from the start of my career. My first encounter with blogging was a partnership with one of Lithuania’s best journalists and thought leaders. My job at an advertising agency involved working with the biggest brands in Lithuania and an incredibly experienced marketing project manager. Meeting Audrius shaped my understanding of what it meant to be both a great programmer and an entrepreneur—he remains an authority figure to me to this day. Working for a U.S. company was about quality, long hours, eliminating mistakes, and delivering results.

The third part of the context is that I was raised by older parents, who had me in their forties. They instilled a deep respect for rules—higher education was a core value, and following rules was fundamental to my character. Throughout my career, no employer ever accused me of being lazy or careless. I always gave my best effort, never arrived late, and if I didn’t know something, I would learn it—driven by curiosity and the desire to be the best.

Still, being a Leo in the zodiac has its influence too.

The fourth part of the context is about role models. With my salary, I bought my first English book—Isaac Watson’s biography of Steve Jobs. Reading about Bill Gates and Steve Ballmer made me believe that a great leader is talented, demanding, tirelessly working day and night, and pushing their employees to reach their full potential. In university, while I saw lazy and untalented peers, my close group of friends was the one who sometimes even corrected our professors and challenged their knowledge.

The fifth part of the context is that talented people always surrounded me. As a child, I didn’t attend kindergarten due to frequent illness. In school, I was placed in the top-performing class in Klaipėda’s Versmės gymnasium, later transferring to Ąžuolyno gymnasium. My peers were consistently above average in intelligence and ambition. Teachers sometimes walk into our classroom and say, “You are all so ambitious and competitive that the tension is palpable.”

When I moved to Kaunas at age 18, my new friends were successful entrepreneurs in their thirties. My peers were always the same—they read, worked, and always took one extra step forward.

The Reality Check

What does all this context mean? It means that in the early years of my career, I never worked with lazy, unmotivated employees with questionable character traits.

Fast-forward to the period I’m describing, and I realize my first employees were not like me. Until then, I had always been surrounded by people better than me. I assumed that any employee I hired would want the same things—work hard, strive, learn, and take initiative when struggling.

It turns out that reality is the opposite.

People like me were the minority once I stepped out of my safe aquarium into the open sea.

How Toxic Leaders Are Born

(1) Believing Everyone Should Be Like You

This belief prevents you from seeing the strengths and differences in others. My old self would have thought they were useless if someone wasn’t as ambitious as I was. But not everyone wants to work 12-hour days or clean toilets. Not everyone is driven by professional growth.

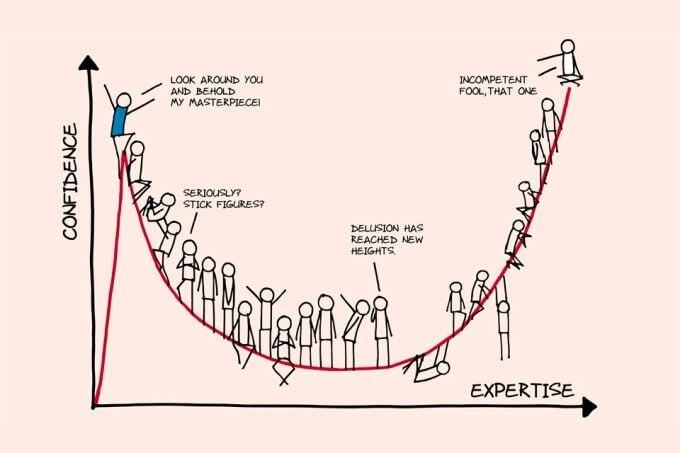

(2) You Don’t Know What You Don’t Know

In my early years as a leader (2015-2017), I assumed people were naturally motivated. I had no idea that a leader must work on motivation. I didn’t understand that employees sometimes don’t see their flaws, and it’s the leader’s job to help them. Simply telling someone to “open their eyes” doesn’t work.

(3) You Lack the Tools

You might need to change When you realize your commands, raised voice, or strict approach don’t work. But how? If you’ve spent your life learning programming and project management, you might not have explored leadership, motivation, and management methodologies.

(4) Changing Old Habits is Hard

It’s one thing to struggle to understand how someone doesn’t know something. But it’s another to forget that your employee might only be encountering the knowledge you accumulated since the age of 16 in their third month of work.

(5) Unrealistic Expectations for Leaders

There’s an unfair expectation that yesterday’s best specialist should automatically become today’s best leader. Unfortunately, reality doesn’t work that way.

My Toxic Leadership

I was a toxic leader for the first three to five years of my company’s existence. I worked 12-hour days, cleaned the office toilets myself, and fought battles without the right tools, knowledge, or understanding. I tried to force employees to be like me.

Imagine being sleep-deprived, exhausted, frustrated, and constantly under pressure while an employee sitting next to you doesn’t even double-check their work. Meanwhile, the client is calling to complain about mistakes.

At that point, you don’t realize that this is your responsibility, that processes need to be put in place, and that feedback sessions, performance indicators, and coaching conversations are necessary. You only know that you must teach the employee not to make mistakes. Would that work for you? No.

Is It Justifiable?

Not. But this is my leadership story, and I cannot erase it.

It was their first job for my first employees—they didn’t know what to do. And I was a leader who didn’t know how to lead. Our collective inexperience didn’t create the best culture, but we achieved results thanks to my values.

In the end, most toxic leaders don’t want to be harmful. A toxic leader is simply someone who lacks leadership competencies. The only difference is whether they are willing to change.

How did I learn from this, and what was my first real step toward becoming a true leader?

That’s a story for the next post.